Woke up this morning to

this post at Little Professor about lost 19th century novelists. It's a subject that comes up a lot whenever I talk to other Victorianists, but which I have only infrequently observed in earlier time periods. It's funny, though, how we (and by we I mean other Victorianists, or 19th-centurists, more broadly) think of lost vs. found. I mean, which groups are we talking about, here, anyway?

For example, Wilkie Collins. Very very popular in his day, and still instantly recognizable to the most average Brit--but rarely taught even to English majors in the states. Trollope is another good one. I rarely hear of him being on syllabi, and he appears known across the pond almost exclusively because of BBC adaptations--people have generally heard of him and have a vague idea that he is someone they

should have read, but if you ask for a list of big-name 19th century novelists he is immediately squashed under DICKENS, ELIOT, HARDY, THACKERY etc. and rarely can anyone remember the titles of his novels (which is really sad, because they have

excellent titles).

Elizabeth Gaskell is another of that list. I might have passed through all my undergraduate years without encountering her had it not been for Christine Cozzens excellent syllabus for a class called 'The Woman Question in Victorian Literature.' We read

Ruth, which I think rarely makes it onto reading lists, overshadowed in the world of 19th-century novels about unwed mothers from the lowerish classes impregnated by rakish members of the upperish classes by

Tess of the D'Ubervilles. In graduate school, I read both

Sylvia's Lovers and

Cranford, and it was not so much any one of them that convinced me of her talent, but the combination of all three. Each is so distinct in style and flavor--

Cranford in particular is a sharp contrast in that it is nearly completely plotless, and yet is quite vibrant and readable, very funny, and seems laden with import even though the greatest plot point is a cow who wears pajamas.

So anyway, at the moment I'm reading

Wives and Daughters, her last and almost-but-not-quite finished novel (I'm sort of looking forward to an unresolved end), which I have to say is pretty much blowing me away. Molly Gibson, the little heroine, is such a perfect character. She's somehow a direct descendent of both Fanny Price and Maggie Tulliver, at once obedient and dull while also managing outbursts of anger, dismay, and defiance. Gaskell's plot is reminiscent of some of the more re-used fairy tales (young, pretty daughter of widower encounters stepmother of dubious motives, stepsister of dubious morals--hijinx insue), but she layers it into a very textured world. Like Eliot, she is fond of in-jokes and jabs, a sarcastic and wry hand pervades, but she's also capable of startlingly astute scenes.

In closing, I'd like to leave y'all with this scene, which shows just how well Gaskell understands the pitfall of the fairytale plotline. Like Cinderella, or Snow White, or any of the other such girls, Molly has received the advice that to cope with her father's approaching marriage it is her responsibilty to accommodate everyone, to be good and self-effacing, to put everyone else's feelings before her own. If she is good, everything will be for the better. She responds:

"'I did try to remember what you said, and to think more of others, but it is so difficult sometimes; you know it is, don't you?'

'Yes,' he said, gravely.... 'It is difficult,' he went on,' but by and by you will be so much happier for it.'

'No, I shan't!' said Molly, shaking her head. 'It will be very dull when I shall have killed myself, as it were, and live only in trying to do, and to be, as other people like. I don't see any end to it. I might as well never have lived. And as for the happiness you speak of, I shall never be happy again.'

There was and unconscious depth in what she said, that Roger did not know how to answer at the moment; it was easier to address himself to the assertion of the girl of seventeen, that she should never be happy again.

'Nonsense: perhaps in ten years' time you will be looking back on the trial as a very light one--who knows?'

'I dare say it seems foolish; perhaps all our earthly trials will apear foolish to us after a while; perhaps whey seem so now to angels. But we are ourselves, you know, and this is

now, not some time to come, a long, long way off. And we are not angels, to be comforted by seeing the ends for which everything is sent.'"

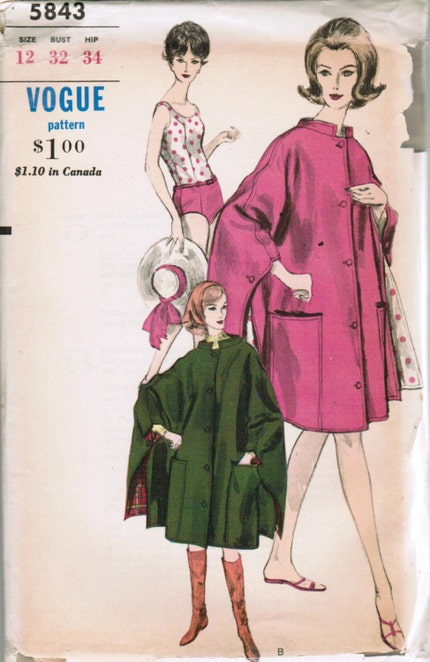

As far as bathing suits go, this one is pretty bleh--drop-waisted bathing suits flatter no one, not even this preternaturally thin Vogue illustration lady--however, all will be forgiven because CAPE!!

As far as bathing suits go, this one is pretty bleh--drop-waisted bathing suits flatter no one, not even this preternaturally thin Vogue illustration lady--however, all will be forgiven because CAPE!!